“Well, I guess it is a rather conceptual work.”

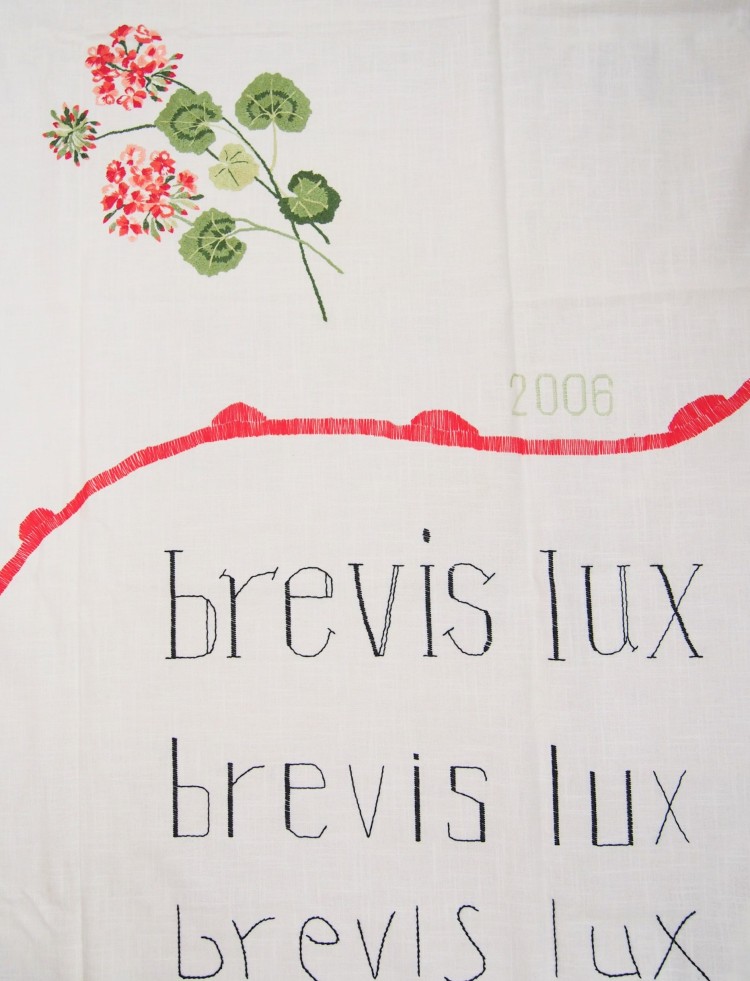

This was one comment about my first artistic piece of textile work, an embroidered vanitas collage that I usually term as the Nobis cum semel occidit brevis lux according to the text stitched on the canvas. I accomplished the work during 2005−2006 as a final part of my BA studies at the University of Lapland, Rovaniemi. Here is a look to the symbols of that work.

“I wished to express ideas about the parallel sensations of archaic continuity and repetitious rhythms often connected to perceptions of traditional rural life and the experience of life’s transience and even the vanity of life.”

Characterising that work as conceptual was agreeable. I had put to it a whole set of viewpoints and conclusions about the contrast between the supra-generational continuity and the momentous nature of life. On the background there were my initial historical studies on craft practices in rural communities, but also my personal pondering about commitments to continuities and about courage to make a new start.

I was 22 and felt that time was flying by. Then again, the making of the piece of embroidered art turned out to be a real time consumer, as I worked on a cloth of 1,80 m by 2,30 m. I remember having embroidered most part of the summer 2005; how I started many sunny summer mornings with a cloud of white linen in my lap stinging the needle repetitiously through the fabric stretched onto a frame. I remember having learned a great deal of persistence and concentration embroidering by hand a motive after another. Actually, I guess that summoned an important lesson in the art of embroidery in the first place.

But during that summer 2005 I also took on another cultural task. I read Väinö Linna‘s trilogy Under the North Star that offers an insightful look to Finnish history from the late 19th century until the post-WWII years. The family saga of three generations covers the essential turns in Finnish history of the time period, but also offers a touching story that easily makes the reader cry tears of compassion and tears of joy, sometimes even at the same time. A part of common cultural knowledge, passages of the trilogy and just lines of dialogue continue to be applied in casual conversations and are sometimes referred to also in research texts.

For the themes of my embroidery project Linna’s work offered food for thought. I wished to express in my work ideas about the parallel sensations of archaic continuity with the repetitious rhythms often connected to perceptions of traditional rural life and the experience of life’s transience and even the vanity of life. Working on my embroidered vanitas project I recalled the words of Elina Koskela after hearing about the losses caused to her by the Winter War: “Ei pidä olla liian kiinni tässä maailmassa” − One must not hold on too tightly onto this world. To me, these words seemed to dress into a humble expression the sorrow of a mother amid the conditions of the Second World War. In this simple line there is also expressed the fragile but very human need to rely on ideas of eternity, the seemingly eternal continuity of moments following each other in time and, on the other hand, the wish of eternity beyond the secular sphere of life.

But in Linna’s work there can be found a more lengthy conversation, actually a monologue, about an imagined divine meeting on the threshold between earthly lives and eternity. This doomsday speech by the novel character Elias Kankaanpää to me seemed to grasp the feelings of many who had (or have) been overrun by life’s merciless axioms and faced with the apparent vanity of life, but that in its compound of pathetic tones and sarcastic sense of humour gives a subtle argument of life ethics. As an unabashed defence for the marginal groups of the society it can be considered worth recollection even in the circumstances of today shadowed by the gloom of state budget cuts and the increasing income and value gaps. The following is a free translation by the blog author.

Listen, you gnomes. You, down there. You think you’re better than Elkku with your crofts and houses, and growing your geraniums. But then just make your sport fields and grow your geraniums. Even the vicar is working on Sunday with that fool of a militarist. Sure, sure. But a time shall come when Our Lord will say: what did you director of souls do? A military chaplain you were and made sport field on Sunday and pestered the poor people of their humble joys… And what did you teacher do. Did you spread enlightenment to the children? Hardly. With a rifle on your back you jumped around like a half-wit… Tut-tut… I say thee, tut-tut. And the rest of you devils will also be said a thing and another. Oh, yes… But then Our Lord will reach out his hand and say: Look at this Elias Kankaanpää. Has he sown and reaped and harvested to granaries? No. That Kankaanpää has not done. He has lived free as a bird, not worrying about tomorrow… You go there, Elias, there is your place. But the rest of you, you go there, your place is there. And will be pretty warm, too… Good. This shall happen, so that you know it, you devils. (Transl. from Väinö Linna (1962), Täällä Pohjantähden alla III, pp. 216−217.)

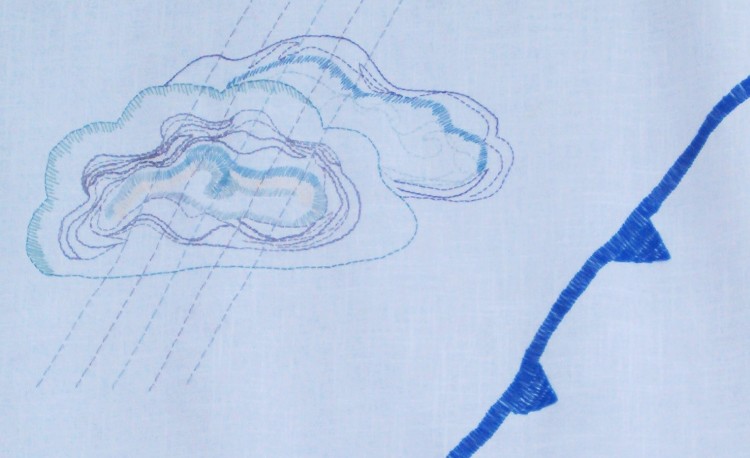

The image of the geraniums on the country house window sill works in Elias‘ doomsday speech as an emblem of the decent rural way of life. (Geraniums possibly still work in that way and not without heaps of nostalgia.) Indeed, such small emblems can be strong symbols of past moments, even of the atmosphere of some bygone days and of ways of life. In my initial embroidery work I collected some of those symbols, the geranium and the butterfly − a Camberwell beauty − as markers of life’s transience. I also embroidered an image of a cow, the object of commitment and the everyday companion to its carer. The life cycle is illustrated in the spiral form on the sun, and yet this transient life takes place in moments, like beams of light between the precipitation fronts following each other.

Along with these symbols I followed the practice of the traditional, embroidered mottos and chose to stitch on the fabric words by Gaius Valerius Catullus of his poem Vivamus, mea Lesbia that remind of the momentous nature of life: as living creatures we only emerge for a short while, like a flicker of light before we sink into the eternal night − nobis cum semel occidit brevis lux, nox est perpetua una dormienda. And this pushes us to the question: what do we do in our time?

So yes, the intention of my embroidery work certainly was of more conceptual than of purely expressive nature. And in many ways, this initial work summoned an ending and a beginning. It was a big thing. It worked as a final project for a period of studies, but it also served for me as the first real step into the art of embroidery. I stitched to it the many thoughts that then orbited on my mind about rural ways of life with its continuities but also with decisive breaks within and away from that sphere of life. Still, it seems that I really did not end working with this piece. Now that I look at it again I would like to add new parts to it and adjust others, and therefore I choose not to show here the work in its entirety.

Back in summer 2006 I nevertheless put the embroidery work on show at the local museum in my homestead, Tervola, to its natural, rural surrounding, so to speak. Perhaps to better communicate the idea of transience of life and the being on thresholds between endings and beginnings I included to the display a poem by Fernando Pessoa, the one dated to the 31st of May 1927. “…But then I already turn / like this field toward itself, toward the day / and the imperfect life.” (Transl. from a Finnish transl. in Fernando Pessoa (2001) En minä aina ole sama, p. 88) And indeed, after having built up the display I packed my backpack, took the passport and the Interrail ticket, and travelled through Europe, from Northern Finland to Southern Portugal. Staring at the horizon on the Atlantic shore there, I enquired after my own life plans and found advice and consolation in Catullus’, Linna’s and in Pessoa’s words.